GB

1936

24mins

Dirs: Harry Watt and Basil Wright

Starring: Staff of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway and the General Post Office

A film documenting the way the post was distributed by train in the 1930s

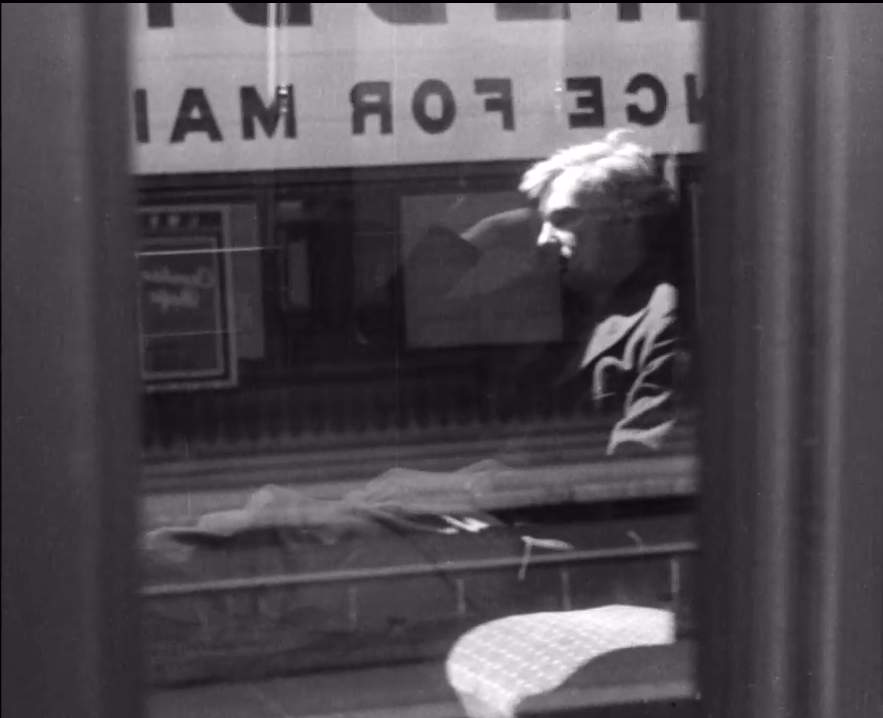

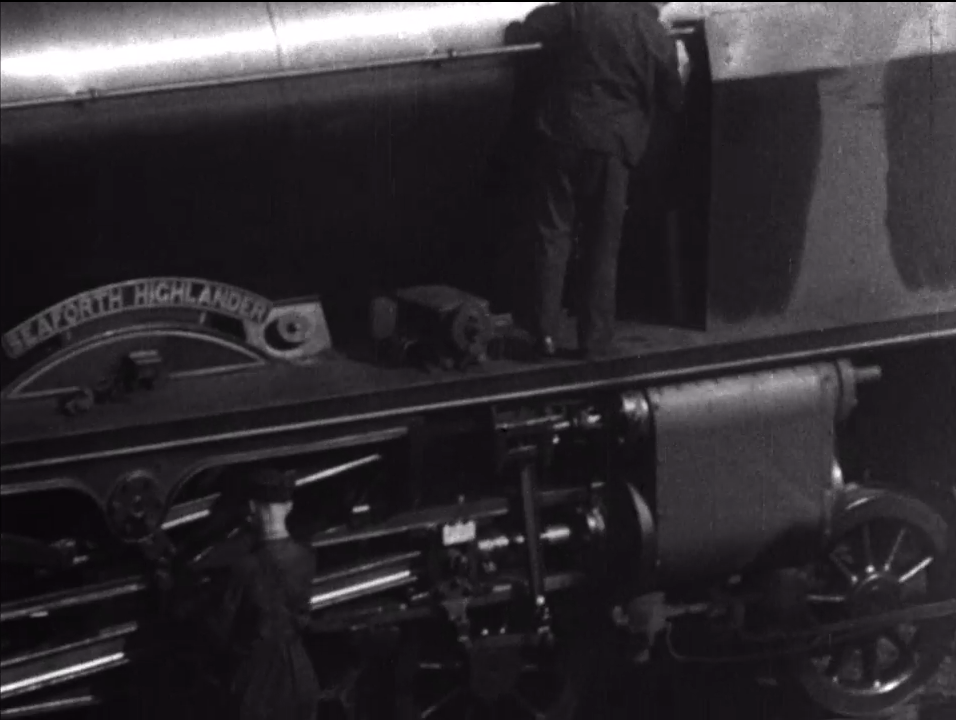

Night Mail is a documentary film about a London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) express mail train from London to Scotland, produced by the GPO Film Unit as their crowning glory. The film ends with a ‘verse commentary’ by W. H. Auden, his now classic Night Mail poem written for existing footage. Benjamin Britten scored the film, which was narrated by John Grierson and Stuart Legg. This was the first film ever to be called a documentary, a word invented by John Grierson for this picture. The film would not normally qualify for such an A-Z but it has become a classic of its own kind, much imitated by adverts and modern film shorts (though the less said about BR’s Night Mail 2 from 1986 the better). Night Mail is widely considered a masterpiece of the British Documentary Film Movement and documents the way the post was distributed by train in the 1930s, focusing on the so-called ‘Postal Special’ train, a train dedicated only to carrying the post and with no members of the public, travelling on the main line route from Euston to Glasgow, and on to Edinburgh and then Aberdeen (or ‘working Glasgow, well-set Edinburgh and granite Aberdeen’ as they are in the poem). There were 40 members of the GPO, or Travelling Post Office sorting personnel onboard. There were seven sorting vans, with six personnel to each van. Each member of the crew would work 48 pigeon holes per shift. External shots include many of the train itself passing at speed with some interesting if somewhat shaky aerial views early on. Although most of the interior shots of the sorting van were actually shot in a studio, as it was the GPO Film Unit Studios at Blackheath accurate recreations of the van interiors could be relied upon. These ‘vans’ were then gently rocked, and the staff requested to walk with a distinctive gait so as to give the illusion of movement. However, much actual footage was blended in with these sets, particularly in the pick up and drop off of mail bags at speed by the specially designed ‘hook and net’ mechanisms on the side of the mail vans, so the whole recreation works well. As recited in the film, the poem’s rhythm imitates the train’s wheels as they clatter over track sections, beginning slowly but picking up speed so that by the time of the penultimate verse the narrator is at a breathless pace. As the train slows toward its destination the final verse is more sedate. All the locos in the film are LMS and the main stars of the show are unrebuilt ‘Patriot’ Class 5XP 4-6-0’s and ‘Royal Scot’ Class 6P 4-6-0’s (control are informed at the beginning that the train is hauled by a ‘Class 6 loco’). There is an excellent ground level view of No.5537 Private E. Sykes V.C. passing a track gang at work on Bushey Troughs and the departure scene from Crewe uses No.5501 Sir Frank Ree. Other locomotives are seen in the footage filmed at Crewe, namely LMS Class 4P ‘Compound’ 4-4-0 No.1078, a Class 5MT ‘Black Five’ 4-6-0, and two shots of Class 5MT ‘Crab’ 2-6-0 No.2933. ‘Black Fives’ appear in a number of run-bys north of the Border and there is a shot of what looks to be a ‘Jubilee’ on the approach to Glasgow Central near the end. A view of the bridge over the Clyde is also seen in this final sequence with at least one tank loco visible. The film ends with a shot of many locomotives stabled at an unidentified shed with the camera focusing in on ‘Royal Scot’ Class 6P 4-6-0, No.6108 Seaforth Highlander, which is being cleaned by shed staff. The stations at Harrow & Wealdstone and Watford Junction also feature and London Broad Street ‘doubled’ for Crewe in one or two night shots including the arrival of ‘Patriot’ No.5513. Several unknown stations appear throughout the early sequence, though one aerial shot shows the train passing north through Bushey & Oxhey and the station at which the local train is shunted clear took place at Cheddington, using the former Aylesbury branch platform. Night Mail’s significance is due to a combination of its aesthetic, commercial and nostalgic success, and several sections have been used as stock footage in other films. The arrival at Broad Street of ‘Patriot’ No.5513 and shots of the departure of the mail from Crewe, for instance, are used in the 1941 movie Inspector Hornleigh Goes to It (qv). Although the film is not without process errors, the most noticeable of which is the arrival of the same ‘Crab’ 2-6-0 at Crewe twice in the space of five minutes and the fact that most of the run-bys feature express trains and not the ‘Postal Special’ at all, it is perhaps a little churlish to comment on these too much and they should not detract in any way from a film that is now well over 80 years old. The 13 minute booked stop at Crewe was particularly well handled and much enjoyment can still be gained by ‘watching the Night Mail crossing the border bringing the cheque and the postal order………’