GB

1929

57mins

Dir: Castleton Knight

Starring: Alec Hurley and Pauline Johnson

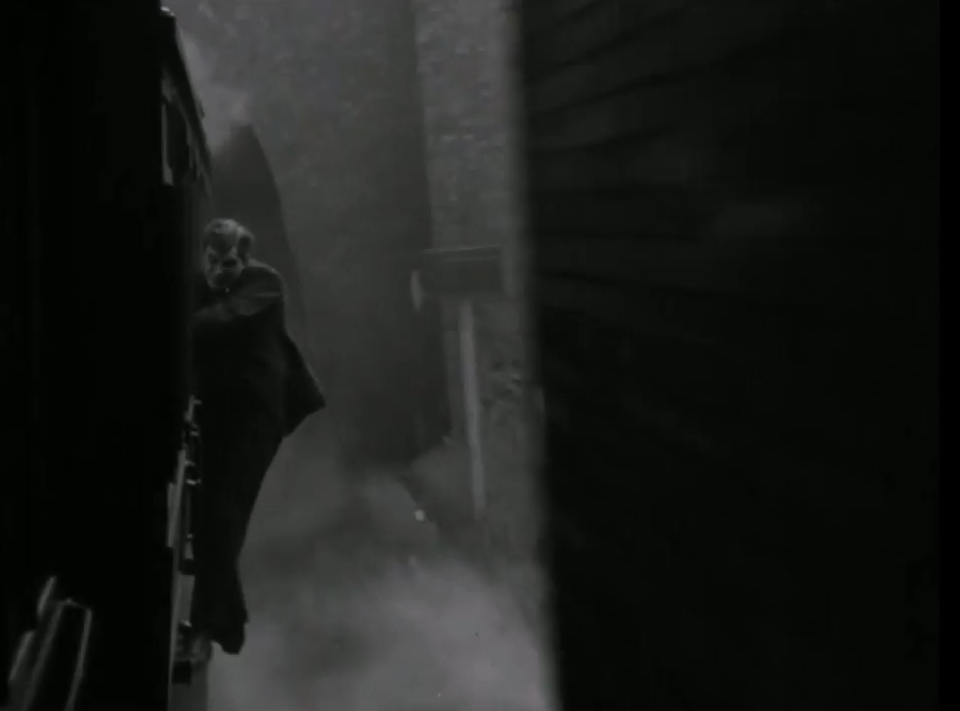

A disgruntled former employee tries to wreck the ‘Flying Scotsman’

This film is a very early ‘part-talkie’ as half way through this silent everyone starts to talk, though this was in fact quite common for motion pictures produced during the transition period. As the name of the film suggests, Gresley LNER A1 Class 4-6-2 No.4472 Flying Scotsman was the star of the film, showing that its recent fame is not a new phenomenon. The locomotive was used by the film company for six weeks of filming, with crews using numerous camera positions on the loco, tender, and stock. The early railway scenes in this film are as follows; A1 Class 4-6-2 No.2565 Merry Hampton passes on an express; Flying Scotsman enters London King’s Cross followed by general station scenes; Flying Scotsman leaving King’s Cross ‘Top Shed’ MPD with ex-GNR ‘large-boilered’ Class C1 4-4-2 No.4411 in the background along with Gresley K3 2-6-0 No.163 (incidentally loco 4411 was involved in the 1935 Welwyn crash but was not damaged); Flying Scotsman backing onto a train at King’s Cross with an LNER N2/4 Class 0-6-2T alongside; Flying Scotsman then leaves with an express, with an N2 on either side, and this is followed by a number of good drivers-eye views of locations in the immediate area such as Gasworks Tunnels and Holloway Bank. During these clips, we get a rare glimpse of a D49 ‘Hunt/Shire’ Class 4-4-0 passing on an express ‘out in the country’. The rest of the film is taken up by the attempt to wreck the train which was filmed on the Hertford Loop. The scenes where actors Pauline Johnson and Alec Hurley climb on to the roof and cling to the running-boards of the train at 45 mph were filmed between Crews Hill, Cuffley, and Bayford, and the actors actually carried out these brave stunts themselves during this stunning sequence, not stunt-doubles. Pauline Johnson wore high-heels! (Pauline Johnson was a leading British silent actress of her age, although she did appear in few films after 1930). The uncoupling sequence began north of Watton-at-Stone and ended north of Stapleford, where Pauline Johnson diverts the approaching carriages from the stationary locomotive by changing a set of points. Having acquired the use of Flying Scotsman, Castleton Knight took a number of liberties, and it is a fantastic record of what could be done through co-operation of the railway companies combining their efforts with a determined film crew. Moore Marriott really drove the locomotive, and Ray Milland actually tended the fire. Eventually the loco is uncoupled from its train, again at speed, and as the loco continues, the teak coaches are brought to a stand. This entire sequence is a masterpiece of editing and in many ways set a precedent for future films. What followed in the 1930s is seen by many to be the great era of British movie making, with Hitchcock’s Number Seventeen (1932) and The 39 Steps of 1935, along with The Last Journey (1936) and the sadly lost Cock O’ The North (1935) (all qv) being other railway movies that vie for attention. After the train has restarted, we get to see a few more locomotives as drivers-eye views take us on the journey towards Edinburgh. These are as follows; an express passes in the hands of another A1, in the form of No.4476 Royal Lancer; a low-level run-by of A1 No.2569 Gladiateur; an arrival scene at Edinburgh Waverley followed by general shots of Flying Scotsman; then a final departure of No.4472 with Reid D29 ‘Scott’ Class 4-4-0 No.9244 Madge Wildfire alongside. Not to be outdone, in an establishing shot of Edinburgh, a City Corporation tram can be seen passing the Scott Monument in Princes Street! However, back to the The Flying Scotsman. The scene of the villain uncoupling the loco from the stock with the carriages racing on in pursuit of the loco were a source of great anger to Sir Nigel Gresley. He said, ‘it made it look as though the LNER had not yet discovered the vacuum brake’ and a special title had to be added to the film explaining that ‘certain liberties had been taken for dramatic license with the normal safety equipment of LNER trains’, which put it mildly to say the least! In fact, this movie put Sir Nigel completely off ‘film people’ as he called them, and he stayed away from the camera thereafter. Footage of him on screen is thus limited to just a few promotional reels from a visit to Doncaster Works in 1927. But these are not the only liberties taken. Note how the driver works the entire journey from London to Scotland without a relief crew, and that after the train restarts, the railway inspector has to take to the footplate because there was no relief fireman! And after all this they arrive in Edinburgh bang on time…… The movie itself is pretty standard fare for the day, except of course for the railway scenes which raise it to an entirely different level altogether. It seems a shame that this movie is relatively little known, despite being readily available on DVD (I of course have a copy). The film has a lasting legacy in that some shots from this production crop up in other films. The shot of No.2569 Gladiateur for instance appears in both Bulldog Drummond At Bay (1937) and Thursday’s Child (1943), whilst the shot of Flying Scotsman moving off shed also appears in the latter.