GB

1953

1hr 24mins

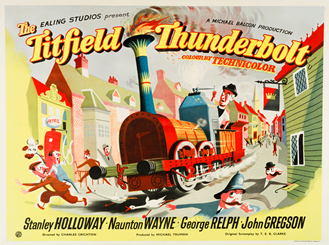

Dir: Charles Crichton

Starring: John Gregson and Stanley Holloway

After British Rail put up a closure notice for their local branch line, the villagers offer to run it themselves

This Technicolor Ealing comedy is one of the best known and best loved of Britain’s railway movies, the fact that the film was shot in colour helps. By showing trains passing through the verdant English countryside in all its finery, it reminds one perfectly of a lost era. The film was shot on the Limpley Stoke-Camerton branch in Somerset, with Monkton Combe as ‘Titfield’ and Bristol Temple Meads as ‘Mallingford’. Thunderbolt, the main star of the film, was 1838-built Liverpool & Manchester Railway 0-4-2 No.57 Lion, at the time the oldest British steam locomotive still capable of being steamed. The loco’s maroon and dark green livery was repainted nursery red and bright green for the film. The famous opening scene was filmed at Midford, where the Somerset & Dorset passed over the Camerton branch, and an S&D express hauled by Bulleid ‘West Country’ Class 4-6-2 No.34043 Combe Martin passes over Midford Viaduct as the branch train passes beneath. The branch train consists of a 1400 Class 0-4-2T hauling an ancient coach, a cattle van, and ‘Toad’ brake van No.W68740 at the rear. Two 1400’s were used in filming, Nos.1401 and 1456, though both were numbered 1401 for continuity purposes. Another 1400 Class in the form of No.1462, appears later in the film when it is stolen from a loco shed. Driven off the turntable and then through the Oxfordshire town of Woodstock, this sequence used a very effectively disguised lorry, the chassis of which is only just about visible in some scenes (though it ‘bounces’ on its suspension which is something that a heavy loco with rigid underframe would not do). A 4500-series 2-6-2T can also be made out in the background of the scenes, which were filmed at Southall shed. The 1400 was stolen as a replacement loco for the one on the branch which was destroyed, along with its coach, in an act of sabotage by the local bus operators. The night-time shots of the train being moved out of the station by Harry Hawkins (played by Sid James) so that it free wheels down the line to crash, were filmed during the daytime using strong filters, although effective enough, the contrast and the shadows give it away as a daytime scene. The crash was filmed in the studio using highly effective scale models. The coach which is used in the early part of the film, until it is ‘wrecked’ in this crash, dated from 1884 when it was one of a pair acquired for use on the Wisbech and Upwell Tramway where they were numbered 7 and 8. After passenger services on the tramway ceased in 1928 they were transferred to the Kelvedon & Tollesbury Light Railway where they remained until that line closed on 5th May 1951. They were then stored at Stratford Depot in East London. No.8 (possibly No.7) was used for filming and was returned to Stratford when filming ended with the intention of preservation, but this did not happen, and it was broken up sometime during 1954. Some tentative evidence has come to light suggesting that the producers had initially planned to use the Tollesbury branch for the setting of the film, then thought against it after they found the branch not to their liking scenery wise. This would lend credence to the use of the Wisbech Tramway coach as that would have been on the Tollesbury branch at the time of their visit to the Essex line. The grounded coach that formed the home of Dan Taylor (played by Hugh Griffith), which is pressed into service after the crash, is a very good studio made prop that was fitted onto a Machinery Flat for use in the consist of the train. The flat wagon is a rare bird in the form of Loriot Y No.41989, built in 1937. One of only two Loriot Y’s ever built, it was later scrapped, though its sister No.41990 was preserved. The town museum from where the ‘Titfield Thunderbolt’ was liberated from was filmed in the old Imperial College building (now demolished) opposite the Royal Albert Hall in South West London. All these shots were made using a studio-built model. There is some apocryphal evidence that this model was held back after the conclusion of filming and passed into BBC ownership when they brought the studios two years later in 1955, but no further evidence of this has come to light. The real Lion was already 114-years old at the time of filming and it was felt that it could not be used in the scene where it is ‘rolled’ down the steps of the museum. Nevertheless, the loco was unfortunately damaged during a heavy shunt in filming, a collision which is clearly visible in the film when the train is bought to a stand at the water tower. It displays evidence of its bent bufferbeam to this day. No longer a viable steaming option, the loco has been placed into peaceful retirement and currently resides in the Museum of Liverpool. Towards the end of the film when Lion joins the main line at Fishers Crossing near Limpley Stoke, what is probably an ex-GWR 4300 Class 2-6-0 roars past on an express, whilst the final climatic scenes take place in the Fish Dock at Bristol Temple Meads station to a chorus of loco whistles. A couple of ‘Castles’ and ‘Halls’ are present in the background of these scenes and although most of these remain sadly unknown one can be identified as No.5036 Lyonshall Castle. Driver Ted Burbidge, fireman Frank Green, and guard Harold Alford were not actors: they were British Railways employees from Westbury depot, provided to operate the branch train on location. Charles Crichton spoke with them during filming and realised they ‘looked and sounded the part’, so they were given speaking roles and duly credited though we only see the fireman once, and very fleetingly, at the beginning of the completed film. Other Western Region footplate staff are visible in the final scenes at Bristol. The steam roller / steam loco battle scene was filmed at the site of the old Dunkerton Colliery near Carlingcott. Despite being well-loved by railway enthusiasts, the critical opinion of ‘Titfield’ has always been rather mixed. The main criticism voiced is that compared to other Ealing comedies it lacks ‘bite’, the satire is rather tame, and it uses eccentric, make believe characters rather than anyone the audience can really identify with. The fact that the volunteers get their financial backing from the local wealthy landowner by telling him they can legally operate a bar while the train is running so he will not have to wait for the local pub to open, only highlights this point! Another criticism is that it celebrates an outdated railway for the sake of it. Although this was eleven years before Beeching’s report on Britain’s railways resulted in rationalisation of Britain’s rail network, BR was already trimming branches, with a number of closures already taking place at the time of filming. The Camerton branch had already shut It lost its sporadic passenger service as early as 1925 and closed permanently to freight in 1951. The overgrown trackbed visible in many shots bears witness to this. The fact that the railway in the film is saved because it is so slow only serves to solidify this feeling. However, what is overlooked is that the film was actually ahead of its time in a number of attitudes. The idea of volunteers taking over and running a railway with ancient stock predates what really began a decade later with the preservation movement. In fact, ‘Titfield’ took considerable inspiration from the book Railway Adventure by established railway author L. T. C. Rolt, published in 1952, about the restoration of the narrow-gauge Talyllyn Railway in North Wales. Most tellingly, perhaps, is the scene which takes place at the public inquiry into the closure of the line where John Gregson gives an impassioned speech about what will happen to the village when the railway closes, and road transport is king. Seen today, it is an astonishingly far-sighted spectacle. Finally, a footnote about Lion. The loco had appeared in a feature film only the year before when it starred in The Lady with a Lamp, but it had also been used in Victoria the Great (1937) and even briefly appears in the 2002 movie 24 Hour Party People (all qv). Meanwhile, a shot of the branch train appeared 13 years later in the 1966 Hammer horror The Reptile (qv).